An international research team, including the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), has successfully deciphered centuries-old inscriptions in the room of the Last Supper in Jerusalem using digital photography. The findings, which include the coat of arms of the Steiermark family, shed new light on the diverse pilgrimages of the Middle Ages.

One of Jerusalem‘s most sacred sites is located on the summit of Mount Zion. Jews and Muslims revere it as the tomb of the biblical King David. According to Christian tradition, Jesus held the Last Supper with his disciples here. Built by the Crusaders and also known as the Cenacle, this hall still attracts pilgrims from all over the world today.

An international research team, with the participation of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) and the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), has now succeeded in documenting and deciphering previously largely unknown inscriptions, coats of arms, and drawings on the walls of the Cenacle. The results have been published as a comprehensive article in the renowned Liber Annuus, the yearbook of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum in Jerusalem.

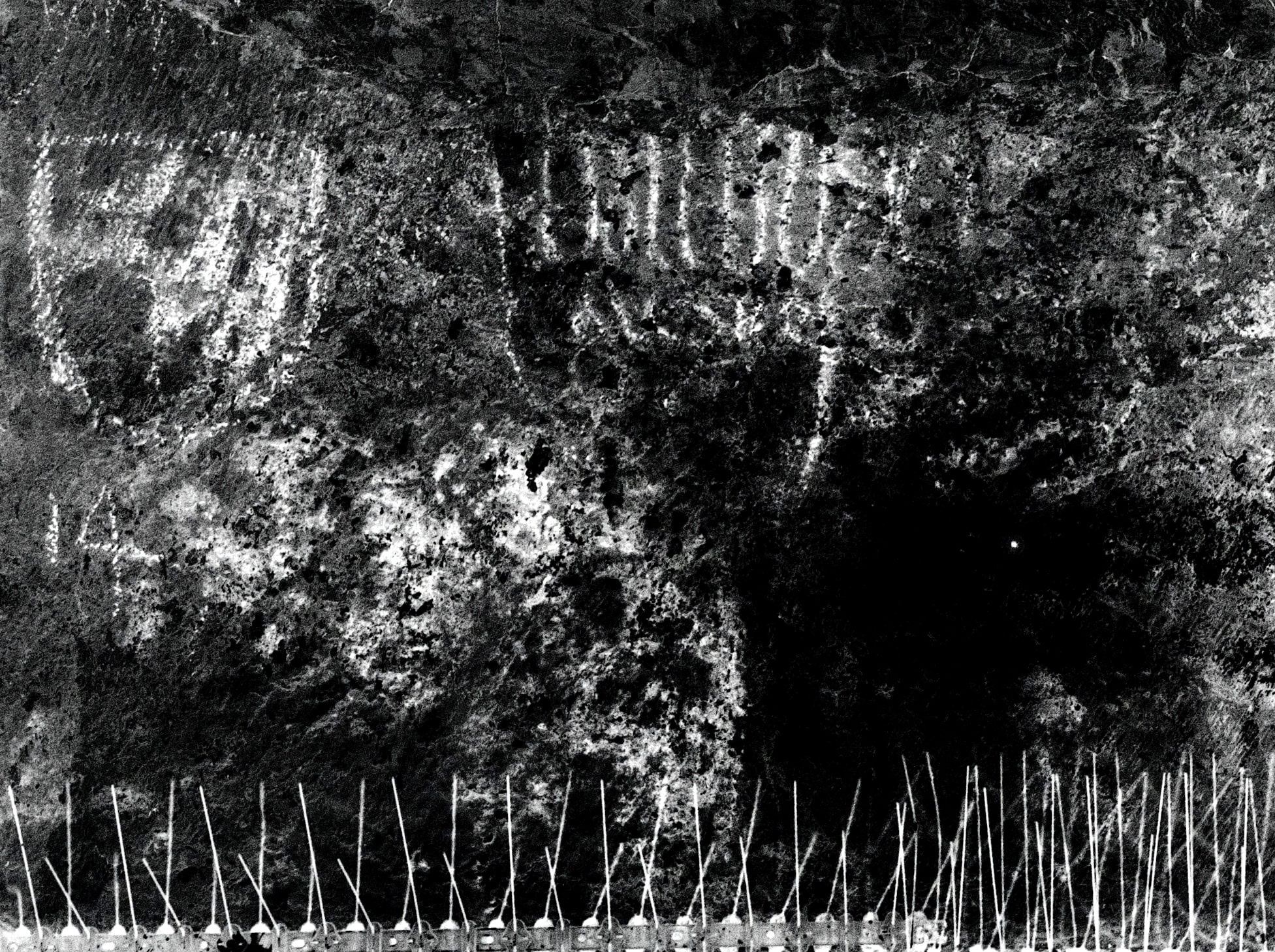

Shai Halevi / Israel Antiquities Authority

The Steiermark Family Coat of Arms in Jerusalem

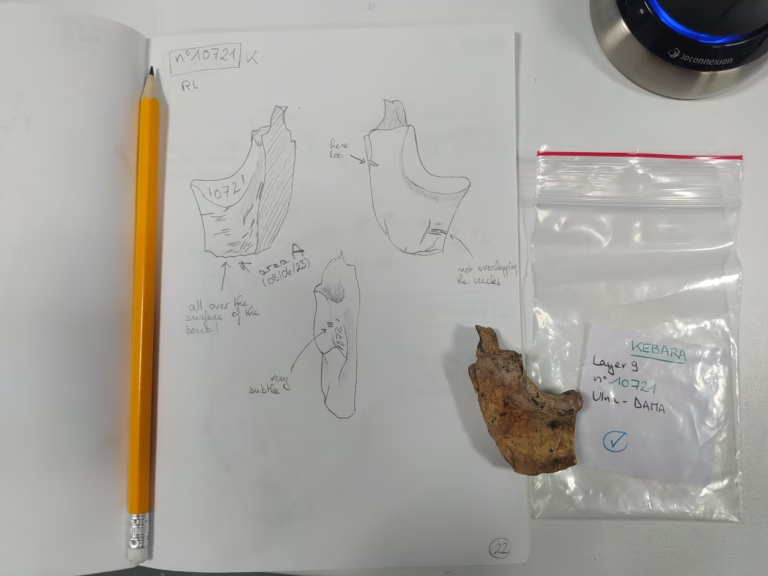

Most of the inscriptions, made visible again through digital processing, date back to the late Middle Ages when the Room of the Last Supper was part of a Franciscan monastery. Of particular interest from an Austrian perspective: in 1436, the Habsburg Archduke and later Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem with 100 Austrian nobles.

One of his companions was Tristram von Teuffenbach from Steiermark. Elements related to his family’s coat of arms can be identified on the assembly wall. Supported by findings from the ÖAW’s long-term research project Corpus Vitrearum, which has been studying medieval stained glass art, the emblem can be clearly attributed to the Murau region in Steiermark.

A Victorious Armenian King

In addition to the Steiermark coat of arms, an Armenian inscription reading “Christmas 1300” is one of the most significant finds. This could clarify a question that has remained unanswered since the 14th century: Did the Armenian King Het’um II and his troops actually reach Jerusalem after their victory at the Battle of Wadi al-Khaznadar in Syria on December 22, 1299? The inscription’s date and its high position on the wall (typical for the epigraphy of Armenian nobles) support this.

Of particular importance is a fragment of an Arabic inscription that reads “…ya al-Ḥalabīya”. Due to the double use of the feminine ending “ya”, researchers concluded that this is graffiti left by a Christian pilgrim from Aleppo, Syria. This is a rare example of female presence in the pre-modern world of pilgrimage.

A Colorful Group of Pilgrims

Finally, the inscriptions and signatures of some well-known figures of the time are also remarkable, such as that of Johannes Poloner of Regensburg, who reported on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1421/22. A charcoal drawing of the coat of arms of the famous Bernese noble family of Rümlingen was also documented.

Besides traces from Armenia, Syria, and the German-speaking world, there are also numerous inscriptions from Serbia, the Czech Republic, and Arabic-speaking Christians from the East. These inscriptions offer unique insights into the origins of pilgrims during that time. “These graffiti shed new light on the geographical diversity and international pilgrimage movements to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages – far beyond the Western-dominated research perspective,” explains Ilya Berkovich, co-author of the ÖAW study.

Cover Photo: The Last Supper Room on Mount Zion. Heritage Conservation Jerusalem Pikiwiki Israel