A recent archaeological study has uncovered surprising new insights into the daily life of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Estonia, revealing that an enigmatic class of bone tools may have served a vital — and previously misunderstood — function: stripping pine bark.

The findings, published in February 2025, are the result of a collaboration between Polish and Estonian archaeologists, combining cutting-edge microscopic wear analysis with hands-on experimental archaeology.

Pulli: Estonia’s Oldest Human Settlement Reveals New Clues

The research centers on the Pulli site, Estonia’s oldest known human settlement, dating back to 9000–8550 BCE. Located near the Pärnu River in southwestern Estonia, Pulli has yielded over 1,100 artifacts, including tools made of flint, bone, antler, and stone.

First excavated in the 1960s, Pulli has long intrigued archaeologists. Among its most puzzling finds are beveled moose bone tools — their function debated for decades.

“These artifacts didn’t quite fit any known category,” said Dr. Heidi Luik, an archaeologist at Tallinn University. “They were expertly crafted, but their wear patterns didn’t resemble chisels or typical woodworking tools.”

A Hands-On Approach: Experimental Archaeology in Action

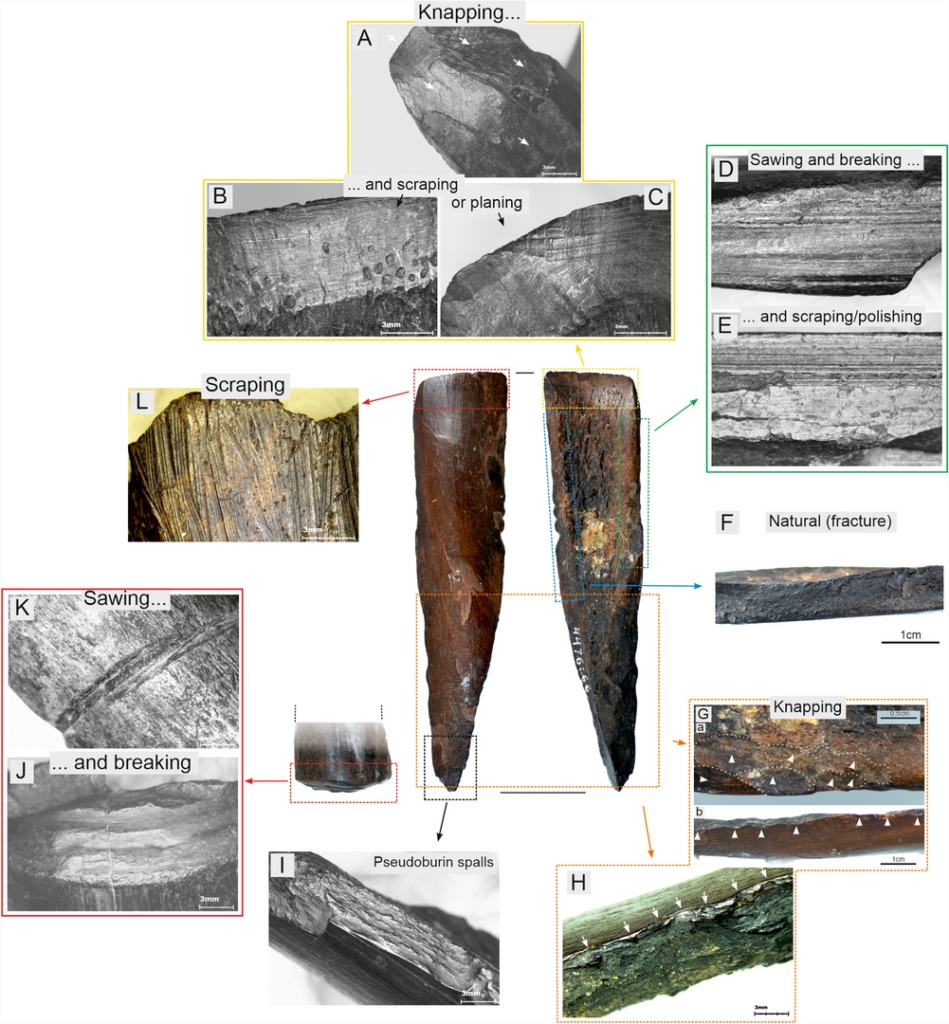

To finally unlock their purpose, the research team, led by Dr. Grzegorz Osipowicz of Nicolaus Copernicus University, turned to experimental archaeology. The team recreated the tools using authentic techniques and tested them on materials including meat, hide, dry and fresh wood, and bark from pine, alder, and birch trees.

The verdict? The wear traces on the original tools closely matched those formed during fresh pine bark stripping. None of the other materials produced comparable patterns.

“It was the pine bark — and only the fresh kind — that left the microscopic marks we also see on the archaeological specimens,” said Osipowicz.

Pine Bark: A Hidden Hero of the Stone Age

Far from being mere tree covering, pine bark in the Mesolithic era may have been used in floatation devices for fishing nets, cordage, baskets, or tool handles — a multipurpose material essential to survival.

Because bark and other plant-based items rarely survive over millennia, the study offers rare evidence of organic technology in prehistoric societies.

“Tools like these give us access to technologies that are otherwise invisible in the archaeological record,” said Luik.

One Tool, Many Uses?

Despite the compelling evidence, researchers acknowledge the tools may have had multiple functions over their lifetimes. Only the last activity may leave visible wear.

“We’ll never be entirely certain,” said Luik. “But this is our best glimpse yet into how Mesolithic people interacted with their environment using organic tools.”

Why This Study Matters

The study not only redefines a class of prehistoric tools but also showcases the power of experimental methods in archaeology. It illustrates how careful scientific analysis can reconstruct everyday behaviors lost to time.

“Even the most modest organic artifacts can reveal profound stories,” said Osipowicz. “The key is knowing how — and what — to ask.”

Osipowicz, G., Lõugas, L., & Luik, H. (2025). Bevel-ended bone artefacts from Pulli, Estonia: Early Mesolithic debarking tools? Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. DOI: 10.1007/s12520-025-02187-6

Cover Image Credit: Grzegorz Osipowicz /Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences