A recent archaeological find near Jerusalem has prompted a reevaluation of long-held beliefs regarding ascetic practices during the Byzantine period. The discovery of a woman’s remains in a grave typically associated with male ascetics raises important questions about the roles of women in the extreme religious traditions of the 5th century AD.

Initially believed to belong to a hermit nun bound in chains, the remains underwent scientific analysis by researchers examining proteins in the dental enamel. Their findings indicate that the grave, dated to the 5th century AD, contained the remains of a woman who practiced self-mortification using iron chains. This significant discovery, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, highlights the role of women in extreme ascetic practices during the Byzantine era.

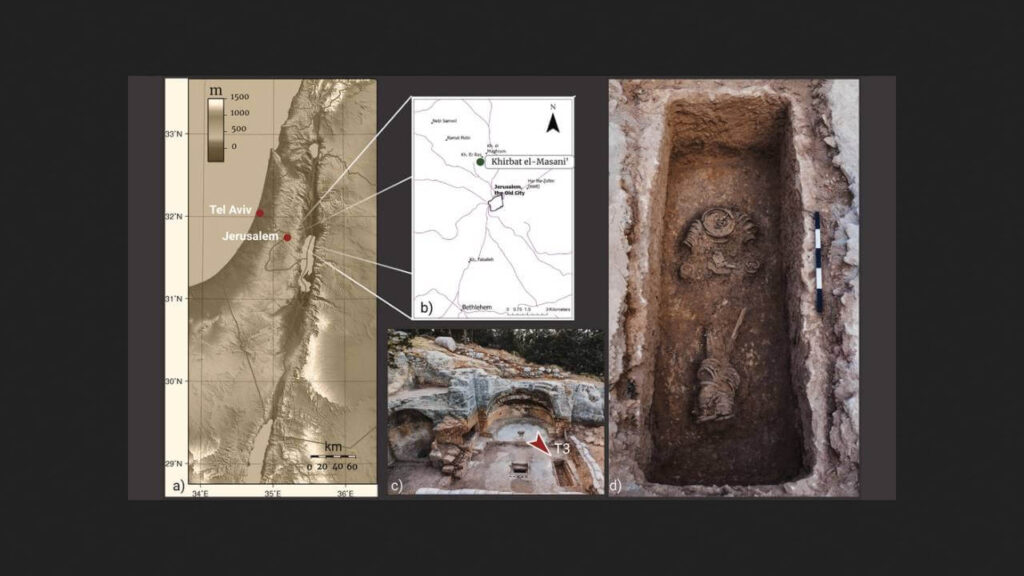

Archaeologists uncovered the remains in the Khirbat el-Masani area, just a few kilometers from the Old City of East Jerusalem, where they found the ruins of a Byzantine monastery dating from 350 to 650 AD. Recent excavations revealed several burials believed to date back to the 5th century. Among these, researchers discovered poorly preserved remains of a man buried with heavy iron chains, typically worn by ascetic monks to restrain their flesh. Notably, instead of a traditional burial, scientists found numerous large metal rings, each approximately ten centimeters in diameter and collectively weighing several dozen kilograms, around the man’s neck, arms, and legs.

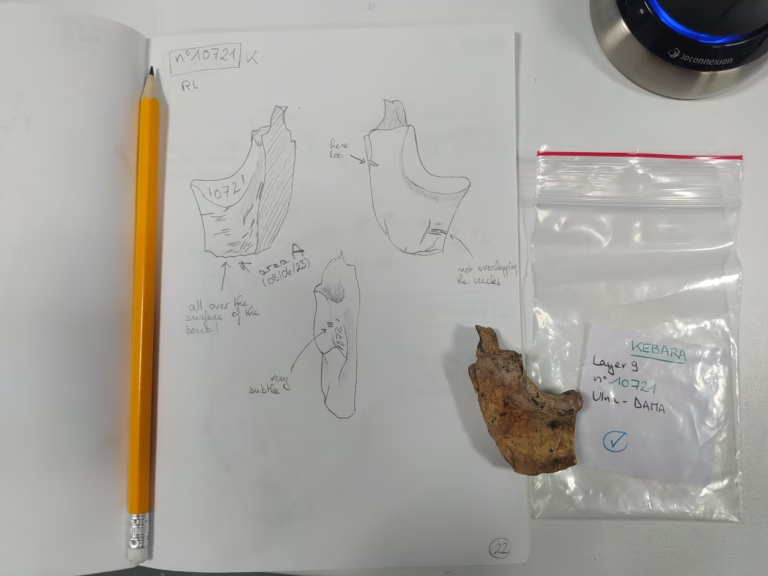

The skeleton of the ascetic monk was found in a highly fragmented state, with only a few bones preserved. Despite this, Paula Kotli from the Weizmann Institute of Science, along with her Israeli colleagues, conducted a comprehensive examination of the remains. Analysis of three preserved cervical vertebrae and a tooth allowed them to determine that the grave likely belonged to an adult aged between 30 and 60 at the time of death.

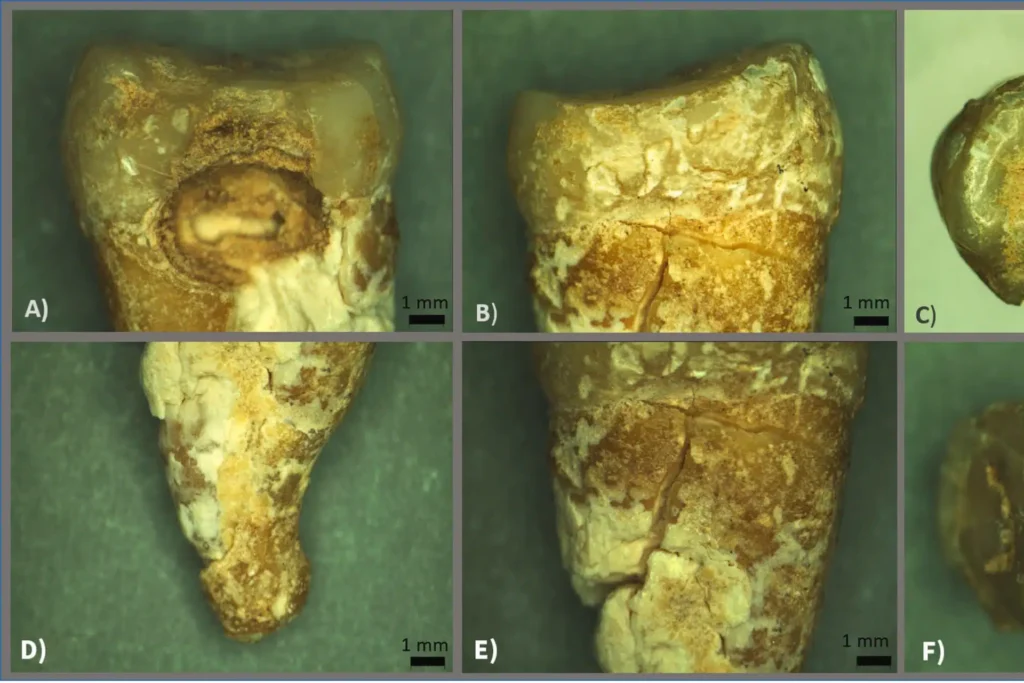

To ascertain the individual’s gender, scientists performed peptide analysis on the remaining tooth, specifically the second upper molar. The results revealed the absence of peptides associated with the AMELY protein, which is coded by a gene on the Y chromosome. In contrast, they identified a significant presence of peptides linked to the AMELX protein, associated with a gene on the X chromosome.

This compelling evidence led researchers to conclude that the grave likely contained the remains of a woman, challenging previous assumptions about the association of the burial with male asceticism. This discovery not only sheds light on the identity of the individual but also raises critical questions about the roles of women in ascetic practices during the Byzantine period, suggesting that women may have engaged in similar extreme religious behaviors as their male counterparts.

According to researchers, historical records indicate that women in the Roman Empire began practicing asceticism as early as the 4th century AD. Notable figures, such as the Christian saint Melania the Elder and her granddaughter Melania the Roman, exemplified this trend by embracing self-discipline to achieve spiritual goals.

However, the burial examined in the scientists’ new paper represents the first archaeological evidence that women in Byzantine society tortured themselves with heavy chains alongside men during that period. This finding not only emphasizes the existence of female ascetics but also challenges traditional narratives surrounding ascetic practices, highlighting the active role women played in these extreme religious behaviors.

The monastery where the grave was found was strategically located along the Christian pilgrimage route to Jerusalem, which became a major religious center during the Byzantine period, attracting worshippers from all corners of the Roman Empire. These monasteries served not only as spiritual sanctuaries but also as havens for weary pilgrims seeking comfort and guidance. In this vibrant context, the presence of a female ascetic challenges conventional perceptions and suggests that women may have played a much more active and rigorous role in these communities than previously acknowledged.

This groundbreaking discovery opens new avenues for understanding the complexities of gender and religious practices in the Byzantine era, inviting further exploration into the lives of women who embraced asceticism in a predominantly male-dominated religious landscape.

Paula Kotli, David Morgenstern, Yossi Nagaret, Corine Katina, Zubair ’Adawi, Kfir Arbiv, Elisabetta Boaretto, Sexing remains of a Byzantine ascetic burial using enamel proteomics. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 62, April 2025, 104972. doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.104972

Cover Image Credit: Paula Kotli / Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports