A new study has revealed that the lunula, a gold ornament unearthed from the Chão de Lamas treasure in Portugal, may hold significant information about the complex timekeeping systems of the Celts. Conducted by Professor Roberto Matesanz Gascón from the University of Valladolid, this groundbreaking research suggests that the lunula contains clues about the synchronization of lunar and solar cycles in the Celtic calendar.

The analysis of the intricate geometric patterns on the crescent-shaped lunula indicates that this artifact could visually represent a 114-year Celtic calendar cycle. This period corresponds to six Metonic cycles, each lasting 19 years, providing a known astronomical framework that facilitates the alignment of lunar and solar calendars. The Coligny calendar, an important epigraphic source dating from the 2nd century in France, offers detailed insights into how the Celts structured time, although the correspondence of these cycles to the 365.24-day tropical year has long been a topic of debate.

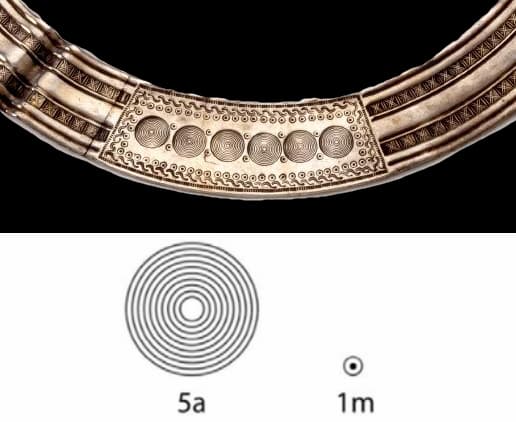

Matesanz’s work is particularly innovative as it establishes a connection between the geometric designs of the Coligny calendar and the Chão de Lamas lunula. He theorizes that the circular motifs on the lunula represent a timekeeping system that adjusts the solar year by subtracting 53 days every 114 years. This intriguing figure of 53 days also appears in Irish literary sources, suggesting a potential link to Celtic traditions in Ireland.

The design of the lunula is not merely decorative; it features large concentric circles and smaller circles with central points, divided into five distinct sections. Matesanz proposes that these elements may correspond to the months in the Celtic calendar’s five-year cycle. The arrangement of these geometric motifs is critical, as the study indicates that the elements of the lunula could symbolize six five-year cycles, each containing 62 months, totaling 30 years. This calculation aligns with what the elder Pliny referred to as the “Celtic saeculum” in his work “Natural History,” resulting in a 53-day surplus compared to the solar cycle.

To address this discrepancy, Matesanz suggests that the Celts may have adjusted their calendars by subtracting these days every 114 years, thereby ensuring that their festivals and astronomical observations remained synchronized with the changing seasons.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this research is the appearance of the 53-day figure in Irish Gaelic texts, particularly in the medieval tale “Baile in Scáil.” In this narrative, the legendary king Conn Cétchathach encounters a magical stone on the Hill of Tara, and the druids state that they cannot reveal his name until 53 days have passed. This period of silence may correspond to the days subtracted to maintain the alignment of the Celtic calendar with the solar year.

If validated, this hypothesis would demonstrate that Celtic oral traditions preserved elements of an ancient time synchronization method even centuries after Roman influence. It would further support the idea that Celtic civilization possessed complex astronomical knowledge, clearly evident in both their artifacts and mythology.

The study also encourages a reevaluation of the role of art as a symbolic language among the Celts. The Chão de Lamas lunula may serve as an example of how they integrated abstract and mathematical concepts into their artistic expressions. Additional archaeological discoveries support this perspective, with similar iconographic objects like the Axtroki vessels and the Leiro helmet in the Iberian Peninsula indicating potential calendrical functions. In Central Europe, artifacts such as Schifferstadt-type gold hats have been interpreted as timekeeping tools, reinforcing the idea of a shared understanding of time among ancient cultures.

Roberto Matesanz Gascón, The lunula with geometric decoration of the treasure of Chão de Lamas and the Celtic calendar. Palaeohispanica, vol.24 (2024). doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v24i1.543

Cover Image Credit: Piero Baguzzi / R. Matesanz / MAN, Ministerio de Cultura de España